DISCONTINUITY

By Roger Koza

There is a mythical image which represents both a historic landmark and a summary for the whole mindset of an era; the greatest Latin-American filmmakers getting together during the well-known Viña del Mar Festival, in the Republic of Chile, in November, 1969. To simply name the Honorary President of the Festival—Ernesto Guevara—is enough to see how unambiguous the symbolic coordinates in those days were. The physician who became a revolutionary was already dead by that time, but his ghost was still present in the collective cultural imagination of any artist active by the end of the 60s. It is impossible to even think of a similar situation in current days.

All filmmakers in the region were present at the Festival—Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, Miguel Littín, Fernando Solanas, Glauber Rocha, and Raúl Ruiz, among others. However, there were also spots for less politically aware filmmakers. Paradoxically, that edition of the Festival would not become the starting point for a continental filmic movement towards emancipation and eventually revolution; rather, it was the unexpected swan song of a collective construction which back then seemed destined to film the arrival of utopia into the world. However, the coups in Argentina, Chile and Brazil, as well as the general political situation in the region throughout the 1970s, contributed to the destitution of this horizontal and pro-Latin-American subjectivity. The experience of those days would never be repeated.

Something deeply disturbing happened in those times of dictatorships. By the mid 1970s, films such as La batalla de Chile, La hora de los hornos, and México: la revolución congelada would become unconceivable because there were no longer conditions to film in such a way by then. And so, the unspoken prohibition re-arranged the collective imagination of both future filmmakers and the new children of democracy in the 1990s. What happened back then was a form of discontinuity, the establishing of a gap, of a distancing, of a collective and subjective mutation.

The most decisive effect had to do with the vast shift in the experiences, mentalities, and worldviews of filmmakers themselves, as well as in the dominating ideas about cinema. To make films in the late 60s meant nothing but wanting to transform all orders of reality. Contemplation and beautiful tales were only a bourgeois distraction which time would eventually dismiss. Cameras were mechanisms for revolution. And, as Eisenstein dreamt, cinema could become a tractor plowing over the psyche of the people, preparing them for a new way of being in this world.

Militaristic infamy finished this kind of cinema. Military regimes were directly responsible for the disappearance of the so-called “Third Cinema.” Some of these filmmakers got killed and others were pushed into exile. However, the greatest perversion imposed by these military regimes was their destitution of a whole era’s collective imagination and the sly manner in which they established a gap in the way possible relations between cinema and the world were understood. This is the quintessential change which audiences of the Yamagata Festival will witness—in the 1960s or the 1970s a film such as Jonathan Perel’s Toponimia would have simply been unthinkable since such pure, structural observation of a social practice had nothing to do with those times of revolution. Back in those days, films were determined by a pressing need of transformation.

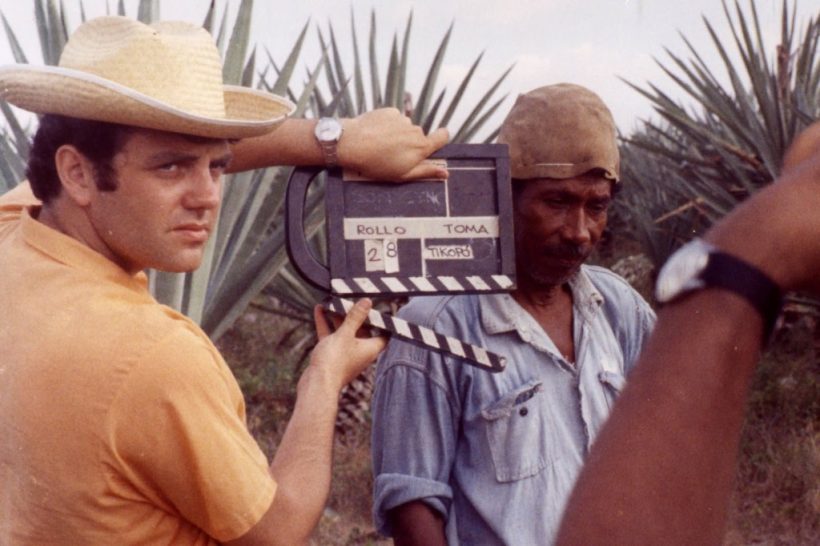

The only element of those days which still stands firm is what we find in the path followed by movies such as Tire dié—a particular sensitivity to film social reality which remained in time. And though not all filmmakers had the ideological clarity and formal precision of Birri or Leonardo Favio, portraits of poverty carried on in films such as Birri’s as well as in others like Crónica de un niño solo or more recent titles such as ¡Qué vivan los crotos! just to name a movie made in a period somewhat closer to ours. After the 1970s, the representation of poverty became a true issue for Latin-American cinema. And that is why a film like Agarrando pueblo—of amazing relevance still today—is so significant. Better than any other, this film foresaw the requirements demanded by the world of power for portraying poverty as a spiritual export good destined for rich people throughout the world to take a peep at a poverty far detached from them.

Some may say–and rightly so–that this film made by Mayolo and Luis Ospina remains current today, no one can refute that; representation of poverty still convinces, touches, and is good to get funds. This is still going on now, decades later, just as it did in 1978. Perhaps nowadays there are a few differences, things that back then would have been completely unconceivable. Back in those days it was enough to simply show Latin-American people as the destitute children of universal dearth. The idea was to establish a glance which would raise a high dose of pity and some pretended moral outrage.

And though the current political relevancy of Agarrando pueblo is completely out of the question—the pornographic depiction of poverty has established a recognizable aesthetics of its own—the true genius in this classic film of disobedience lies on the way it questions filmic representation as such. By establishing a separation between a documentary register in black-and-white and another one in color—supposedly, this latter is the film being shot by some Colombian filmmakers for a German TV channel—Mayolo (and Luis Ospina) gobble up this divide in their own film and saturate the devise right to its chore. An extreme close up on Mayolo’s eye peeping through a hole becomes a pivotal point and first warning about the intrusion of fiction in the realm of documentary (and vice versa); this shot is followed by the arrival of a remarkable character who not only reacts to the fraud committed by the fabrication of an aesthetics of poverty but also introduces himself as a sign of the destitution of any principle of purity in any form of representation. To film and to represent always entail an arrangement of truth following an order built upon elements rooted in the collective imagination. In this sense, the participation—at the end of the film—of a homeless man (real or not) alters the epistemological contract between the viewer and what is being presented on the screen. However, this is no hindrance for glimpses of truth being shown through the way the staging of the farce is put into action.

An undisputed master piece of political cinema, it shows a humorous lack of political correctness, as well as an impious discourse and a formal finesse which are normally absent in both satiric and denounce films. An example of it are the decisions in terms of the frames used throughout the film’s last sequence, which represent a whole introduction on the subject which any aspiring filmmaker should take into account.

Latin-American Films Turn to Intimate Naturalism and Family

Things would never again be quite like in those days. And although since the turn of the century the whole region has experienced a considerable degree of re-politicization, Latin-American filmmakers stopped thinking about themselves as a collective entity unified by a common destiny. Also, they are no longer informed and concerned by the issue of mobilizing the masses. The People, as the articulating subject of cinema in its dual role of protagonist and spectator, has practically disappeared, especially if we draw a comparison between its present character and the defining character it had in former decades. So, political cinema no longer represents a way to bring about an unavoidable change and to work towards revolution and its future; let alone a pleasant form of pedagogical adjustment between the New Man and a backward, stagnant consciousness within an individualistic and subjective shape which could no longer exist in the revolutionary future. All of these things belong to the past now. Today’s tasks are different, less urgent but also more reflexive—to review the past, to reconstruct it and to question it in order to avoid its repetition while also repairing the quality of family and intimate life in nations where social tissue was deeply, mortally, wounded. Most political films in the last two decades are narrated in the first person and family stands as an institution capable of establishing links between the sphere of intimacy and the sphere of politics.

A good example of this is La sensibilidad. Scelso, a documentary filmmaker who seems to have specialized in shooting portraits, chooses now to point his camera towards his own, and rather complicated, family history; his father, Jorge Scelso, was murdered at a clandestine detention center during the days of the military regime while Sara, his mother, miraculously survived. However, this is not at attempt at therapeutic closure, a private and political exorcism shown in front of an audience; no, this is rather a superb sociologic work applied to a symbolic microcosm in which the subject of memory can be seen and conceptualized from a whole new perspective for Argentinean cinema.

With clarity and assuming risks, the director reconstructs a (present) past and questions sensitivity as such. His thesis is that sensitivity depends less on genetic capacities or specific personalities than on class background. How does he prove this thesis? He uses his two grandmothers, Laura and María Luisa, an aristocrat and a working-class housewife, who allow him to explore into the depths of sensitivity and its nature—a common historic experience and a shared family tragedy are not quite the same when seen from such opposing points of view. From everyday moments (the music they hear, the way they cook, the TV shows they watch) to the most intimate and grievous experiences, Scelso discovers class signs are undeletable traits, an involuntary symbolic force which determines their experiencing conditions. The central idea is great and, in spite of its austerity of resources, the final film stands up to this greatness.

Another related example is Aldo Garay’s latest film, El hombre nuevo (The New Man), a very pertinent title. In this movie, the Uruguayan director casually brings together the life of Roberto who is now Stephanie —a Nicaraguan woman who currently lives in Montevideo and wants to have an operation to fulfill her wish to fully become a woman—with her revolutionary past in the 80s. The key word for Garay’s film is transformation.

El hombre nuevo is truly a film which grows in complexity while it becomes almost impossible to guess all the turns the tale takes as it finds its own way to unfold. Depending on the hidden richness of a character that keeps his story zealously to his own and doesn’t tell much about it, Garay’s fixed, stern shots offer a counterpoint to a story which opens with a homeless transvestite and ends with the history of Nicaragua (and a visit to the protagonist’s home country), the failure of a revolution, and the discreet triumph of religion. Stephanie’s trip to her native country is marked by the arrival into the plot of a set of characters who offer unexpected warmth and social perspective.

Garay avoids using interviews and goes for staged moments where his character meets with his mother, his brother, and several childhood acquaintances. Registering the geographic space of these meetings is not overlooked by a director who uses few, but precise, resources to establish relationships between a specific space and its people. Stock material becomes crucial and at some point Garay finds an old TV broadcast piece which establishes a new order in the way we understand the protagonist. This is a great filmic moment, of an impossible-to-miss emotional effectiveness when dealing with a touching revelation about the protagonist’s childhood.

Gustavo Fontán’s films are not political—if sensitivity as such is not conceived as a political issue. But if sensitivity—devastated by a system of permanent audiovisual alienation—is conceived differently, then El árbol is a first-class political film.

It might be perplexing to find a film where the crux of the narration depends on an old couple’s constant argument about whether or not they should cut down one of the acacia trees at the front of their house. Parting from a (poetic) register of his parent’s everyday life, beginning in the Spring of 2004 and ending in the Fall, in 2005, Gustavo Fontán manages to capture the process through which a decision is taken and its results, which can be verified (through the sound) at the last second of the film.

The whole movie is set in a house in Banfield, in the south of the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires. However, while the decision about the tree is postponed the dominating emotion is not claustrophobia but some sort of naturalistic joy which transforms that home into a stage of cosmic dimensions. El árbol is part of a filmic tradition in which contemplation becomes a working method through which the physical beauty of the world is found through those things which though visible are not quite seen. A shot of some bees by a tree, ants floating on rain puddles in the patio, the storm hitting against a window—all of these become traces of the future. The passage in which the old couple goes to sleep and then the tic-tac of the living-room clock becomes omnipresent is a summary of the obsession to apprehend the present time in all of its duration; this astonishing moment is announced by a scene in which the couple sees some slides, and the director’s poetics of sound is fully appreciated.

Fontán unveils the power of cinema to spy time, its duration, and the mutation of all living creatures in it. A poetic course is announced right from the beginning through a quote by Juan L. Ortiz, a poet from the Argentinean province of Entre Ríos. El árbol is a meditation on inhabiting, which entails unveiling the structural relation between time and being. “Poetically dwells man on this earth,” said Hölderlin; this is a quotation Ortiz could have written too, and which Fontán brings into matter effortlessly.

Within our current coordinates, João Moreira Salles’s Santiago is a fundamental film. Here, the political aspect is related to discovering class consciousness as the only way to build any perspective in cinema. And it is true the greatest challenge for any filmmaker who attempts to film a social reality different to his or her own is to question (and to put into evidence) his or her own class awareness, expressed through the staging of his or her films.

João Moreira Salles, brother of well-known director Walter Salles (Motorcycle Diaries) and son of a diplomatist and minister, chooses to take up an old project—the filmic portrait of his butler, a man from the Argentinean countryside who lived for decades with the director’s aristocratic family in a mansion in Rio de Janeiro. This lonely man—slightly effeminate and owner of a portentous memory—was not only fluent in six different languages and loved Giotto’s paintings and Wagner’s music but he also devoted his life to writing a 30,000 page universal history of the world’s aristocracy; this bizarre hobby for a servant stands in perfect dialectic accordance to Salles’ attempt to film them, and while Santiago’s interventions are of an existential and encyclopedic nature, Salles’ off-screen participations are poetical and philosophical.

Santiago is a filmic wonder, an irreplaceable master class of cinema. When the director states (or rather confesses) why he never uses close ups of his protagonist’s face, the precise meaning of this staging is revealed. Deleuze used to say shots represent the consciousness of a director and none other film I know of embodies that abstract and yet palpable—and even wise—statement better than Santiago, which is moving in its warning about how difficult it is to imagine the lives of others.

Within the context of the new Latin-American democracies a new form of political cinema has to do with capturing the mentality of a precise moment in time. Eduardo Coutinho was the great master of the present moment and the mentalities of a time. His extraordinary film Edificio Master offers a paradigm of his procedures.

Throughout a week, Coutinho and his crew explored a 300-appartment building right in the middle of the Copacabana neighborhood, one block away from the beach in Rio de Janeiro. Through interviews with the building dwellers he composed a collective, multigenerational portrait which allows glances at some traits of a specific social class’ psyche as well as at the unrepeatable mystery of each human being.

Coutinho’s method is simple—using the own words of those being interviewed, the director almost never misses a chance to ask about everything any lighthearted statement might entail and fail to express. The intimacy achieved between the characters and the camera is admirable, and a confessional tone tends to take over as everyone participates in the Socratic game proposed by the director—from the doorkeeper who says he applies the Piaget method and if that doesn’t work he then applies the Pinochet method, to a hooker, an emotional stutter, old couples, musicians, and even a former airline employee who once had the opportunity to sing alongside Frank Sinatra. The result is both magnificent and moving, a true lesson on filmic austerity.

The turn towards intimate, family matters is still the dominating mode but attempts to distance from it have been made by films of denounce, deconstruction, and conceptual reconfiguration. A good example of it is Propaganda, a film made by MAFI (Filmic Map of a Country). These initials stand for a whole collective, but behind it we find Christopher Murray, an interesting Chilean filmmaker who also authored another rather mysterious film, Manuel de Ribera.

In 60 minutes, Murray and 16 young filmmakers attempt to show—using the methods of observational documentary—the presidential campaign in the most recent Chilean election, held in November, 2013. Fixed shots, sometimes bombastic and sometimes of virtuoso quality, are there simply to observe various situations during the campaigns of presidential candidates Michelle Bachelet, Franco Parisi Fernández, Roxana Miranda Meneses, and Evelyn Matthei, among others.

Propaganda is also quick to reveal a general problem in all democratic systems; the people’s representatives in parliament seem not only detached from their constituents, but also pressured under the demands of a representative system more akin to the world of entertainment. Instead of public officers, politicians become performers who deliver their propaganda not without a sense of drama and some humorous sequences. The position of the camera—almost always from a distance and semi-hidden—underlines a characterization of politics as permanent simulation and although this might be an unhappy verdict it is also a good starting point to question representative democracy.

* This essay was comisioned by Yamagata Film Festival in 2015 and it was published in English and Japanese. The original was translated bt Tiosha Bojorquez.

Roger Koza / Copyleft 2016

Últimos Comentarios