MES FICUNAM 2016 (28) / SHORT REVIEWS (19): L’AQUARIUM ET LA NATION / THE AQUARIUM AND THE NATION

L’aquarium et la nation, Jean-Marie Straub, Suiza-Francia, 2015

Straub insists to mitigate triviality, which is always near cinema, although never near this filmmaker that now shoots, unwillingly, alone. The gullible and the impatient are exasperated. They shouldn’t, because the power of this new film is relentless: an idea, a form, and perhaps the enunciation of a hope, or of a non-negotiable value. How to film The People, a supposedly outdated protagonist? In less than 32 minutes, Straub manages to do so and exposes it without highlights.

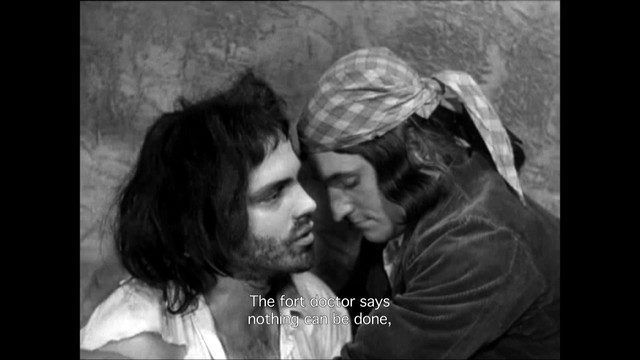

Three fragments, four scenes. First, silence, or the degree zero of sound, until the most complex form of sound organization (a piece of classical music) bursts in a still shot of a fish tank in which several coldwater fish are merely moving in their aquatic medium. In the second segment, as it happened in Kom- munisten, a text by André Malraux will be interpreted—in this case, the novel Les noyers de l’Altenburg, fragments of which will be quoted, from page 98 to 105. The text refers symbolically to the fish, as it also refers to the marvelous two-scene fragment of the first hour of Jean Renoir’s La Marseillaise. The novel is from 1948, the film from 1938; these are not innocent dates, since in those years an idea of a nation was instituted in perversion and lust for extermination.

If the chosen text questions the existence of a sign that makes men equal beyond time and space, the importance of what is said here must be put in the context of the time of the appearance of that book and that film. In the face of the affirmation that an organizing concept for the lives of men that exceeds all cultures subsists, the act of constituting a community or a state, to singularize that universal trait as “the fraternal unity of a people” is not done in vain, more so when “fish can’t easily see their own aquarium.”

An unusual recording rigor is added to the conceptual precision. Watch then how the exterior and the interior of the fish tank interact almost unperceivably, when the talking “fish”, Aimé Agnel, (a Jungian psychoanalyst who has himself written about John Ford’s cinema) reads the passages of the novel. His immobility coincides with the stillness of the garden. But one shot will change the light and the wind will blow a little. That is the right and chosen moment for a philosophical culmination. With another filmmaker, this would undoubtedly be a coincidence, but with Straub the uttering of a single word is as determining as the movement of a single branch on a tree.

English Version by Tiosha Bojorquez

Roger Koza / Copyleft 2016

Últimos Comentarios